This video was created on March 14, 2017

You can download the transcript of this video here.

Was created by Eurasia Partnership Foundation

Transcribed by Ani Babayan

Transcription completed on March 29, 2017

Gevorg Ter-Gabrielyan (GTG) – This is Armenia 3.0, our Jam session, and we are talking about the situation in Armenia. It’s called 20th century Armenia, but we moved into the 21st century as well, and talked about the situation in post-Soviet Armenia in some respects. And our main idea has been, of course, to express the problems and to, kind of, give a diagnosis of, at least sketchy diagnosis of a situation, to explain, in my opinion, in the opinion of some of the people who are in the audience: why did these tendencies that are today becoming more and more obvious, win over? Where did these tendencies come from?

And, of course, the other thing that we should remember all the time: that this is a very sketch account, this is not a scholarly, scientific account. This is just giving some methodological elements of the situation to orientate.

And we are talking a lot about the voids[1], about the things that have not been studied well enough, about the big gaps in our understanding of Armenia. And we explain why did these gaps exist.

Because, coming back to this picture that I was drawing earlier, if you don’t have normal society, then, of course, you also don’t have a normal public opinion, and if you don’t have a normal public opinion, then any research, any knowledge, any expertise doesn’t become public knowledge, it stays in the niches.

So, it is very important to build public opinion, to decide on what is explaining the situation, and what to do, and where to move from now.

We have talked a lot about the origins of the situation, we gave quite a bleak picture of it, probably, especially during last broadcast[2], because we brought together all of the elements of the situation.

But I don’t think this is that much of a bleak picture, because, when I am reading, like, the novel ‘Ragtime’ of the American author, Doctorow, for instance, which is about 1930s and is based on a real story; or… (What was the English title of that famous novel?). ‘Вся королевская рать’ (All the King's Men), also another very famous novel by Robert Penn Warren… you can say that in the United States you have had very much the same situation. Of course, Armenia is smaller, which makes it more dangerous, but also it is easier to manage, it is easier to overcome the problems that exist here.

So, we just have to keep it in mind, that this is not something tragic, it is more or less the situation.

Now what to do? In the previous broadcast[3] we have already talked about the types of corruption, for instance, that exist; and obviously these types have to be tackled.

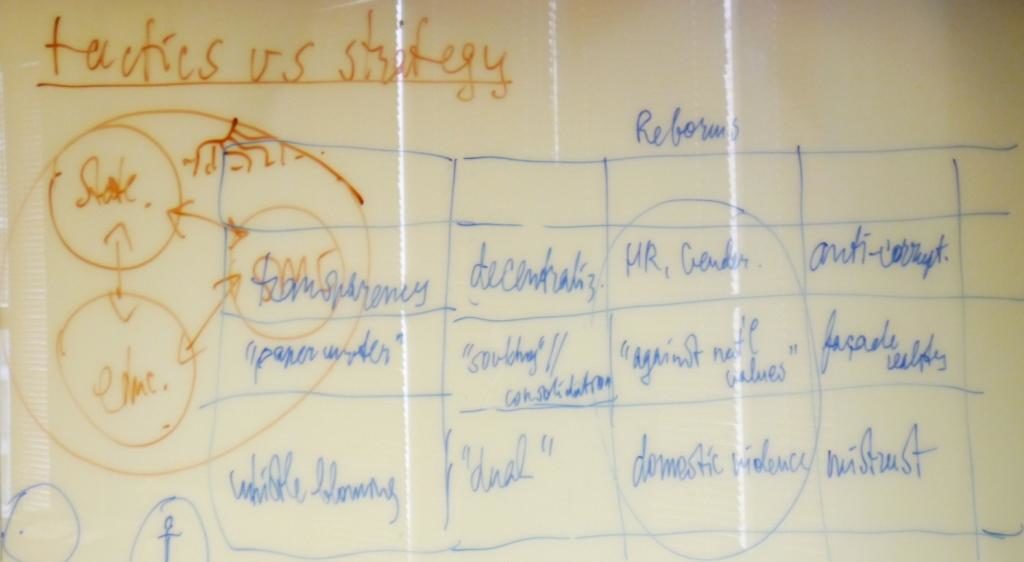

And we can have here tactical approach and strategic approach. And that’s very important to keep in mind, the difference between the two, because sometimes the wrong tactic kills the right strategy, and sometimes the tactic is decided as if to correspond to the strategy, but in fact it is not corresponding to the big strategy. It is killing the big strategy. So tactics versus strategy, I think these two concepts are very important, we have to keep them in mind.

I will give just one example right now. Coming to the elections as observers is tactical, and is tactically a very correct thing. Because if elections are fair, even in the situation where you don’t have good political programs and reliable party alliances, if elections are fair, the overall situation, the overall temperature will become better. If they are not fair, then registering it by neutral people, people from outside is very important. But that is tactical.

Strategically, I have said it already in one of the previous broadcasts[4], the problem with corruption is that it is not going to go away, as long as state employees receive salaries which are not sufficient for them to survive even as individuals, not to say about their families. As long as that situation continues. I am not talking about very high salaries, I’m talking about decent salaries, salaries that allow people to survive modestly, if there is no big emergency and without engaging in corrupt schemes.

So, as long as we have that situation that state people are not being paid well enough (and this is the situation which started since 1989-1990 when the Soviet ruble started to collapse), we will not have a breakthrough in the corruption situation.

Because people are rational. And if you are not being paid enough, you start doing the things entrepreneurially. Whether you are corrupt or not, that is a different issue, but instead of being devoted to your work, maybe you start a business on the side, even if you don’t use your administrative capacities for that. But moreover, when you see that you can use your administrative capacities, you start using your administrative capacities for your own personal gain. So, this is very typical, this is one of these traps of all the poor societies. And I think we, Armenians, are smart enough to somehow tackle this. When Sahakashvili came to power, he tackled this not fully, sustainably, but quite thoroughly in some respects. Because George Soros and some other donors started to pay salaries for the state employees; and that gave him an opportunity to fire many. Like the police reform that he did, it means and it is the same police reform that has happened in the United States in 1950s.

You fire the majority of the police force, or all of the police force; you make lesser positions with higher salaries; very strong tests, very strong exams to come back to service. Some from the old police are recruited back, some new people are recruited, the rest are retrained and go to live their lives in another area.

So, I’ve already drawn that picture, just to remind: this means actually three interrelated circles: business (small and medium enterprise), education and state. So, people from the state, who are being let out, have to receive special education to get new opportunities to go in the business and anywhere else and whatever they want to do. And people who stay in the state structures are more responsible, receive more funding, do more work, which makes sense; rather than end up in this trap of bureaucratic, byzantine-like procedures and forms and stuff like that.

So, this is one major zoomed out picture of the reform that has to take place, if we want to change the situation in Armenia. This is one of the major elements of that reform. And that again brings us back to the education, that brings us back to culture, that brings us back to tackling the blatnoy[5] culture, reforming the entire educational system; building public opinion, getting knowledge out of the niches; and making it belonging to the larger network, to the larger society; and all these things.

And, of course, I am not giving recipes, because that means we have to sit down and think on how to reform this education system. What does it mean to reform the education system?

And we should sit down and think how to redraw the state structure, the organigram of the state; and everything: which positions to keep, which positions to get out. And you know that rhizome[6] has a tendency to expand. That’s why Armenia has one of the most, per capita, one of the biggest amount of police people, or policemen, in the world. Not only because the state wants to be a police state, but also because becoming a policeman means somehow making the ends meet. I already told about that.

So, this reform of the state: letting out people, giving them good educational opportunities, helping them to go into private spheres, in other spheres, is a way forward. It may sound very difficult, but it can be done.

The second methodological element that I want to mention is, again, in this logic of tactic versus strategy. I am going to draw it here, because it is going be some kind of a table, probably. So, let’s try to draw that table.

We already said that every time we start to reform, we try to do a reform, we are facing three levels of the situation, three levels which affect the situation: (1) the global issues, the global approaches, the global elements; (2) post-Soviet: a major part of our talk has been devoted to this. Because the global and (3) the national are more known. When I was talking about the blatnoy culture and when Rob was talking about the merger, the intertwining of the national and post-Soviet tradition[7], or Mikayel was talking about that, it is all because we are lacking, so far, a very good and clear understanding of the post-Soviet element in this triad.

And now we take a reform. Reforms are here (the rows), reforms or things to change, or good ideas, or good projects are here.

And I have prepared some examples, but we can go together through these examples. Like, I don’t know: let’s take the element of the human rights strategy or of the equality of men and women, equality in gender issues. Domestic violence, we now have the situation where we have to tackle the domestic violence. As you know this law on domestic violence is being discussed right now. And the state, in order to pass it through, because they want to correspond to the European standards, and they receive funding from them, so they decided to pass this law somehow, but suddenly the state itself publishes amazingly daunting sociological result, which demonstrates that… I don’t exactly remember the numbers. Bella, do you remember the numbers?

Isabella Sargsyan (IS) – 18% of all killings are domestic violence cases.

GTG – So, 18 % of all killings in Armenia, for many years, are domestic violence, based on domestic violence, and that means 6 killings out of…

IS – That means each sixth killing.

GTG – Each sixth killing, every sixth killing is on the domestic violence ground. And that’s the statistics that has been published by the state itself, so we can assume that it is higher in reality. Unless the state decided to give such a daunting picture, again for a, kind of, speculative interest (to make this law likely to pass).

So, we have this problem, which is a national level problem, very much intertwined with the post-Soviet. And look how things change, so we are talking about gender, human rights, etc. The global level, right?

And then we see that the post-Soviet in us, in the Armenian society claims that having such a law is against the family values. So, using the national rhetoric, but it is actually the post-Soviet which claims that. Okay? So, ‘it’s against national values, it is going to ruin our family, it’s going to bring the situation where kids are being taken into the care and away from their parents’, etc., etc.

Exactly the same arguments that Russia used recently to decriminalize some elements of domestic violence. So, see what happens here. If we don’t take into account the post-Soviet element, we will either have ruined the chance to adopt, the chance to adopt the law on domestic violence, or we may even have a backlash. We may have a situation when domestic violence will be decriminalized as it happened in Russia.

And for every kind of reform we have this situation. So, if you are only zooming in on this issue, this is tactics. If you are zooming out and taking into account the big picture here, how are these three layers interrelated, only then you become strategic.

That means not just to adopt the law, but to adopt the law, finding correct arguments against this argument (that it is ‘ruining the family’), and with a lot of work on policy advocacy in the society. Because many people who say that this is ‘against national values’ are like this (post-soviet), they are not honest. But some people are like this, many people are like this (nationalist, undereducated): they are just being confused, because of the lowering the quality of the education and (because of) everything that we talked about.

Another reform: anti-corruption. Again, a global fight against corruption takes place; many international organizations are (engaged). For that Armenia has signed several agreements with the international structures: that it will fight corruption. And then what we have at the national level. Because of corruption we have this huge level of mistrust, but not only because of corruption, right? Also because of the fact that the post-Soviet in us, in the Armenians, allows us to build a façade reality: when we say one thing and do another thing, and present another reality.

So, every time there is an anti-corruption project, we somehow ‘suck off’ its positive edge out of it, build a façade reality, as if we fought corruption. Mistrust at the national level increases, increases towards anti-corruption, as well as (towards) anything which comes from the international community and from the global values. Because they see one thing said, another thing done. So, as a result, corruption in its generic sense becomes even bigger thanks to our fight against corruption.

Of course, not always, now, if it’s a good project, even if it takes a small aim to implement, if it zooms out and if it is all three elements here in its interrelationship, so that it chooses something to do which is fighting the façade reality, doesn’t let it to constitute it, which helps not to increase mistrust in global values. And it’s a good project[8].

But very often our projects have been not like that; and that is why for 20 years we have actually a downwards development vis-à-vis corruption rather than a positive development.

Okay, now I’ll go to this side (of the white board), there’s more space here, and I’ll give another example. I already talked about the fact that whistle blowing or, you know, giving information about something negative, some criminal act, reporting has become unfashionable in Armenia, despite the fact that the donos culture was so prominent. So because it is called donos, so you see how the essence, the meaning of the concept changes in this situation of the blatnoy culture.

So, we are talking about, at the global level we are talking about the need in transparency, which, of course, presupposes that if you see something wrong you have to report. Obviously here, at the national level it would mean the whistle blowing culture, and the security for those who blow the whistle, the encouragement for blowing the whistle. But because of the post-Soviet condition we have this negative attitude to that, this: “don’t become somebody who writes a paper. Don’t take the skeletons out of the closet”. So paper writer: “You are a paper writer, you are reporting something that shouldn’t have been reported”. Okay?

And again, if we want to make these values stronger, we have to zoom out and to think about building the culture of whistle blowing in such a way that means the authority of the individual, that means the individual, the integrity of the individual who is whistleblowing. So that the positive results of this whistle blowing are much bigger than the negative results of writing complaints about people with no reason for that.

That also means a special media culture, so that the media is reporting fairly not just attacking somebody because they are allowed to do that, etc.

So, this is, in fact, much more difficult to do than just to do one or another or a third project on this. To do a (strategic) project on this requires some deep thinking, to put some deep thinking into that.

And I can continue on that. I hope we will also discuss some other examples with you. And the last example that I have prepared is, not even the last one, but one of them is… Okay, I’m going to remove this (writings inside the table) because we understand what we are talking about: the global, post-Soviet and national levels.

So, let’s take freedom of expression. Again, another example that in another way I have put when I was talking about the rhizome. Freedom of expression that means you are speaking up about issues. And if it means there’s a need in action, the action is taken by the relevant groups, authorities, etc. Now, of course, we already talked about that at the national level. We have, because of the post-Soviet system, because of the post-Soviet condition, we have no division of authorities, no serious division of powers, and we have talked about that. Judge: the way the judge behaves in this part of the world versus in the West, and many other cases, right?

So, in the situation where we don’t have a division in powers, any kind of a complaint, any kind of information about something which went wrong, is left unattended. Which results in further deepening of the crisis. Because people lose faith in the fact that words mean something. And one of the consequences of this is the electoral bribes.

Because if people in their right mind, even if not well educated people, agree to take 10,000 drams for voting for somebody, that means they are being paid seven lumas per day for the next 5 years, every day seven, if I remember correctly the math that I saw. So 10.000 drams is equal to 365 times 5, divided to 10.000, that makes something like 7[9] lumas per day. Which means that’s as much as they rationally calculate the worth for them as citizens of somebody being elected to power.

That means there is no trust whatsoever that this somebody, who is being elected in the power, would participate in the power distribution in the correct way, in the division of power in the correct way, to react to the needs of the society, expressed via freedom of expression.

Again, if we are thinking about a project (on Freedom of Expression), we should think about this element of that. We shouldn’t just promote freedom of expression. Because if it increases without the adjustment, without connection with deeds, then there is no sense in that, the words become useless. And that is why political parties today may use many different words, but most of them don’t use any convincing words. Because there are no more convincing words left.

Okay, these are some of the examples that I brought. If you have any other examples or want to make any comment, please go ahead.

Mikayel Hovhannisyan (MH) – Decentralization as a reform which is, so in the upper part it will become decentralization.

GTG – Where should I put it? Okay it doesn’t matter; I’m taking this off: decentralization.

MH – It is a reform that is aimed at distributing power more evenly and to giving it to the local levels. On the post-Soviet thought level it is associated with this old Soviet sovkhoz, kolkhoz and that kind of stuff, which doesn’t have anything to do with the local self-government.

And plus the party system comes on top of that; which means that it is basically equal to local branch of the ruling party in an almost single party system. Because the ruling party has for a long period of time been the absolute majority. It doesn’t need any other political forces’ support.

And on the national level it becomes this, again, the division, the dualist thinking: when you introduce something which is not so, as something that is so. So, when you introduce a process which doesn’t have anything to do with decentralization as a reform, as “giving more power to the local authorities”, etc., etc.

On a practical level this is illustrated via the dissemination of the resources. Because the state level keeps all the resources. It doesn’t give any significant possibility for the local level to collect resources for itself, and keeps the local level on dependence. Because the overwhelming majority of local budget is composed of the ‘dotatios’ (subsidies from the state), from the ‘dotatios’ from the central budget.

So, this whole thing again, the whole decentralization reform is basically turned from top to bottom, on local level, on national level, using this post-Soviet mentality.

GTG – Yeah, and I’ll add here that the argument of the authorities is: ‘Let’s consolidate the communities so that they have more power to be decentralized’, meaning to have more decision making capacity. But in fact, they are using the consolidation, or there is a threat of consolidation to be used to make it easier to govern from top.

MH – Because they are not, they are not giving them more resources for that consolidated governance. So decentralization played the opposite role of decentralizing.

Artak Ayunts (AA) – Before bringing examples or trying to understand I am having a little bit difficulty of depicting the situation in a way that what are we trying to scrutinize here? It appears to me when we are talking about this global human values and universal values on the top level, right?, and all of a sudden it is on the national level we practice something that looks contrary to the opposite of global human values, like freedom of speech, freedom of expression, anti-discrimination. All of a sudden I am having a problem understanding it in a way that on the national level it is all opposite. And we want to change something, to bring more positive change. But the perception among many, because of also the media level of the Soviet, post-Soviet mentality, is not providing this conducive environment to undertake these reforms.

On the other hand, these reforms are being, so to say, “dictated” by the donors, if we want to integrate into the society, into the global society, or Western society. And we also have the Russian presence, and the Russian influence, trying, probably, to revive the post-Soviet, or current Russian… I mean to revive the post-Soviet mentality.

And again on the national level we are facing this problem of bribes and vote buying. And people are very reluctant in understanding why we are going into elections; and (they are) just getting some money. And after all this why should people be interested in it?

I am not trying to make a direct connection between taking, you know, this 10.000 dram and global reforms. But it appears that if a person is ready to, you know, to pay this, to get this seven lumas a day, why should they care at all about, like implementing all these global reforms for the better future?

So, I think that we are missing some link here, and trying to understand what the global perspectives are, how the post-Soviet level influences the national understanding and perception of these global reforms.

And the practice is that we, that we do every day, especially during election period, so like delegating all the power to these corrupt criminal blatnoys, and expecting also for the civil society organizations to do some projects that eventually will not be strategic, because of the existence of, sheer existence of the facts that we witness, particularly during elections.

I am sorry, maybe I couldn’t bring all together what I wanted to express. But to me we are sort of missing some important element of understanding: what should be done, like, in strategy rather than tactics, to bring the desired change.

Maybe I made it even more complicated, but I just want to understand in peace-building what are the levels; and that is why I wanted to share (these thoughts) before exercising, before going into the exercise of understanding why we need to do peace-building; and also how it is tactical and strategic in our current projects.

MH – Actually, just in continuation of what I am trying to somehow answer, on my behalf, to what you (Artak) were saying. Actually, as I see the logic of this table, and from that tactics to this strategic thing, is that basically ‘above’ the national level… both post-Soviet and global levels are ‘above’ the national level. And they are contradicting each other; and due to the extreme adaptiveness of the Armenian society, and of the Armenian nation, this dualistic thing immediately appears.

Because you want to, let’s put it this way, you want to ‘please’ both tendencies at the same time. So you imitate the global level, but still you don’t do anything to satisfy the post-Soviet element (to tackle it, to fight it). And that’s what makes the problem on the national level. That’s what creates the imitative process of implementation of any reform in Armenia. Because of this clash of two upper level logics, let’s say.

And from this, if we are coming to the tactics and strategy, I think what is strategic here, is to separate the real processes from the fake processes. And try to, let’s say, making the real processes stronger, and avoiding people to be influenced; and the reform in general; from the influence of these fake processes. And that, I think, what the strategy should look like. And tactically, I think, here it may sound strange, but in this context education is part of tactics, the main part of tactics.

GTG – Strategy, it is strategic.

MH – It is in this bigger strategy, education is a tactical process of approaching (the bigger strategy).

AA – To me the picture, I am really sorry, but to make the picture more simple. At least to my understanding. Would it be correct to name the global level the Western level? I made some references to this in my previous speech. And the post-Soviet level – the current Russian level. I mean, is this the influences of these, that you were talking: the Western values clashing with the post-Soviet, or Russian, current Russian, or Putinist?..

Yeah, but these simplifications sometimes help. And then on the national level we try to understand how to integrate to the Western value system without compromises, without security compromises, with the other level, which is the Russian level. Because in all… everything that we were talking today is very relevant apart from the thing that… exactly the same thing that I just made a reference to. Because we probably underestimate the security condition, or don’t take into much consideration the security condition, and the situation of the unresolved conflicts, and how they affect the perception of people in trying to implement any reforms and achieve any changes in our society.

IS – Maybe I make now picture even more complicated, but I think everything what has been said, I mean all these reforms, Western, or Russian, or whatever, is, to the extent, simulacrums. I mean, to the extent, they are empty forms. Also because, as you said, there’s no public opinion, and there’s no recent reforms that work well. So we, I don’t think we know the society well, I don’t think that we understand people well.

Also because of this bipolarity, if I may say, you know, in those terms (meaning both the West-Russia divide; as well as the concept of dualism).

But also because, if we look into elections, if you want, we all have this perception that people are taking bribes, that people are demoralized, that people are going to vote or not vote for all these fake or whatever parties. But reality shows that, first of all the government, or the ruling elites are very much afraid of the society. And that’s why they do all the falsifications and fraud. Because if they knew that people are totally demoralized; and that they are totally already in the slavery; or that totally this rhizome works, as if, then they wouldn’t need all this machinery of falsifications.

Why? Because people, in the end of the day, they come to the polling stations, and they vote the way they vote. I think that even makes it even more complicated, but for understanding it: I am not sure that people don’t understand that anti-corruption measures should be taken. They do understand it well; (even if) being part of rhizome, being part of the corruption.

I mean, I don’t think, Artak jan, that there is such a clear cut distinction between Western values, local values, Soviet values. To me the missing link is good understanding of the society we live. Because it is changing all the time. And, of course, security constraints, they affected. But due to many, many patterns, including lack of trust, also lack of trust to interviewer, lack of trust to sociology, lack of trust to everything, we don’t know well.

I mean we don’t know well, in the end of the day, people who get into this precinct, people hwo get into the voting boots, how do they vote. Because we have never seen any clear results.

What we know for sure that in those precincts that there were trusted people, who could somehow safeguard the votes, these elites never won. That we know for sure from the referenda, at least. That is the only hard data that we can look into. That in those polling stations where there was good control, people were voting against the government. That’s the only indicator that we had. All the rest are just assumptions.

I think this is the starting point we should look into. And to the extent… I agree that we deliver, we delegate blatnoys to make these Western reforms. This is a bit of a strange thing. But we should understand it better. And that’s why all these series of Armenia 3.0 gives a larger understanding from different perspectives: how to look into this society, and understand it.

The message also goes to the Diaspora. And because they are going to observe the elections, not in huge numbers, but in some numbers, it will be good for them also to understand: where do they come, and what is going to be the value-added. So, if you are in this precinct and have no clue of where you are, even tactically, it might do more harm than good, if you don’t know what you should do in this particular environment, knowing all this rhizome, etc.

That’s why I appreciate this, also from this very particular elections observation perspective.

But going back to Artak’s opinion, I understand it makes things more complicated, but to me, we don’t know: we don’t know whether these people are blatnoy, or it is a hybrid, or these people are totally demoralized; or these people are true believers. Who these people are?

We have no clue of our society, because we don’t know.

MH – Just coming back to Artak’s differentiation putting West and Russia. Why I think global and post-Soviet is a more correct way of calling it? Because global means integrative, so it has the power of integration in itself. While Western is simply a geographic direction. If we talk about post-Soviet: it is disintegrative, because it is based on a collapsed identity, that’s why it is disintegrative. So, that’s why I think this way of calling these two terms is a more correct version to call all these processes.

GTG – Thank you! So many interesting comments. So, what I am going to do now as the last element in this chat, I am going to redraw this picture, this table, to a certain extent, to relate to the comments. Not to reply, not to argue against or in favor, but just to relate to the comments.

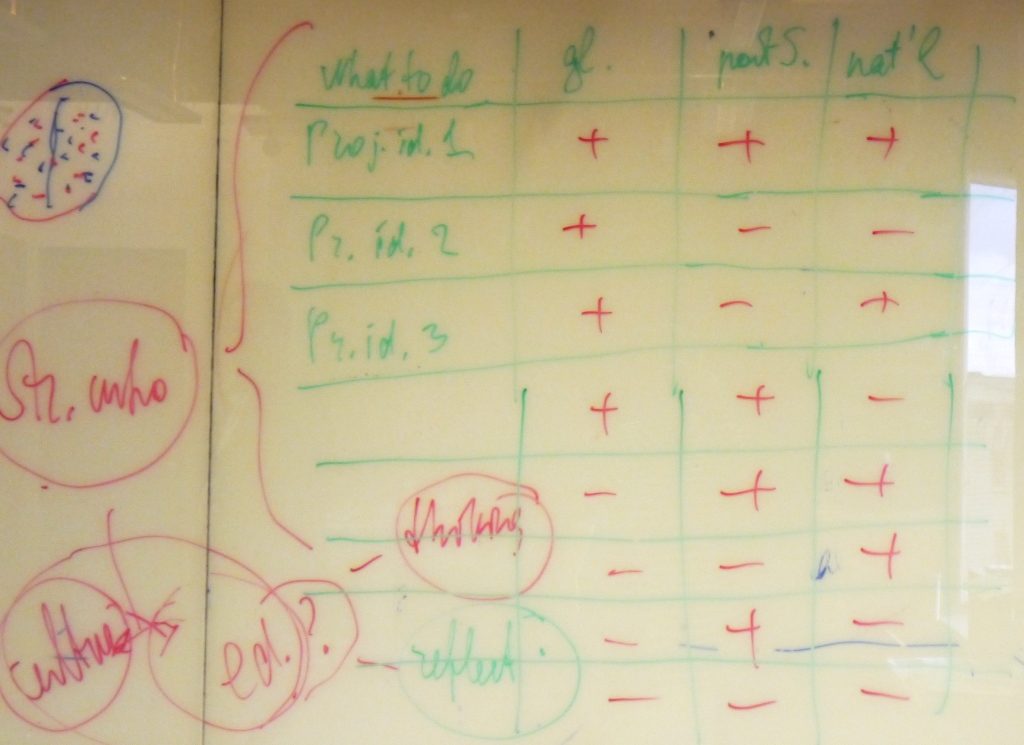

So, we will have to somehow make a bit of a space here. And imagine this picture in a different way, probably these two, so we are having three levels, we are having project ideas, what to do, what to do: project idea 1, project idea 2, project idea 3, etc.

And then we look at the three dimensions: global, post-Soviet, and national.

And we evaluate each project idea. What will be its impact, or its relation with, what will result from it, if we look at it from the perspective of global, post-Soviet, national.

And when I say global I mean my personal choice is more towards global rather than Western. But also I mean values, which are quite empty, I mean values, like human rights, like something which is obviously, at least in my perspective, the basis, the foundation for the development of the human kind.

Because if we continue on thinking along these lines we have to ask us questions: what is the sense, is there a meaning in life, or in life of the humanity. So, yes: there is a meaning: it is to develop as an all-human society of the entire earth; to become better and better; to learn what the universe is about; and all these nice things.

From that perspective the values of human rights, anti-corruption, etc., they all contribute to progress; and progress contributes to health; and health contributes to happiness; and happiness contributes to more creativity. I’m making all these big jumps, but this is kind of, you know, this is a worldview, this is not anything scientific.

Post-Soviet is more, indeed, about all of the stuff that we talked so many times, and many of the things that we talked about. You mentioned (Artak), we have already touched upon also Karabakh, the conflict issue, and I would be interested in you doing this exercise, at least for the Karabakh example, after I finish.

So, but who is doing this all? Of course, it is the guy or the girl who I call ‘the strategic who’.

And who is this strategic who? There is only one, and that is also, Artak jan, to a certain extent, replying to what you were saying: the strategic who is a conglomerate of these islands (the connections between ‘uninfected’ red dots-individuals in the rhizome) in the best case. It is either one, or a bit of a more of a network, or a larger network. This is the strategic who. Who does what? He or she has very special education, which is our enigma, right? What kind of education do we need to make it all work?

Who knows what they know and what they don’t. Knows, they don’t say the word “I know that I don’t know anything”. They say it, but at least they know that they don’t know anything. So, they can act upon what they know. And what does it mean? That means they have reflective capacities, they have thinking capacities. And that’s what they get from education, right? They have learned to think, which almost nobody ever learns, there are no explicit studies for thinking; apart from the way we do it now and in some other cases; they have reflection: they reflect on things, they self-reflect.

So it’s not necessary to have sociological research: you don’t trust a sociological research; you trust your knowledge about all the previous sociological researches that you looked at; what you have observed yourself; the stuff you know about; this sociological research; and eventually you make a pragmatic choice: to trust it more or less; and to make it a basis for your action.

This is all more inside the person than about the objectively existing knowledge. The person or the institution, because ‘the strategic who’ is, of course, it may be an institution as well.

So this ‘strategic who’ takes a project idea and says: well, at the global level it sounds hypocritical not to allow to make jokes, that Armenians like so much, about different nationalities, etc.

At the post-Soviet level it was, at some point in time, in the Soviet times, it was helpful to deal with the reality: all these jokes. And they were, very often, what is called today ‘politically incorrect’, was called ‘dissident’ in the previous times; and it was called ‘politically dangerous’, not just incorrect, because you could be prosecuted for them. And in the national level it is the humor that the Armenian nation has, which is a value. And not only the Armenian nation, but we definitely know that there are different types of humors, right?

So, what kind of projects should we do to address these three things in the most positive way? Something like this.

We choose the project, put it in this, look, and if we have a situation where it is plus, plus, plus, so it is contributing to the global reform, to the nice things globally, taking care of the post-Soviet effects, and also developing the nation, then it’s a good project.

You can now evaluate all the possible versions here, right? It can be like this, this can be like this, it can be like this, it can be like this, like this and like this (-Also all minuses). Or all minuses.

So, and you can, see, you can give names to every case of this. For instance, this is a positive project (when all three are pluses). It’s definitely worth doing it. If it is not addressing these two (post-Soviet and national), it’s a global issue, like, for instance, there are, sometimes, international organizations which are supporting, I don’t know, working against HIV/AIDS, in a society where there’s no almost HIV/AIDS. I’m not saying they are supporting the way it’s needed, I am saying they are supporting in an exaggerated way, because of bad strategies. Then you have something like this. When it’s not touching really national issues. It’s not touching post-Soviet issues. It is positive for the global issues, but because of this (not touching the other two), it is not eventually positive.

When you have this (addressing the global and the national without touching the post-soviet), this is a façade reality, when it’s not touching the post-Soviet issues, even if it’s very good for the nation: like this anti-corruption example, or whatever: it is globally correct, but if you don’t address the post-Soviet, it becomes fake, façade reality.

Here (addressing a global and a post-Soviet issue), I don’t know; it is quite controversial. It may be both positive, but also not very positive, because when it’s a global issue and it’s addressing the post-Soviet realities, like this fight against fake news…

MH – I think that when the minus is in the third row (he means column), it is… that project is hardly to be adapted in the Armenian situation. I think the third row (national) relates to the adaptation in general.

GTG – Well, okay, but you can make this into plus, you have to think how to adjust such a project for the Armenian reality. And we in our experience, in our office, do it very often, because we engage in international projects making the Armenian part of it very special, to make it adjusted to the Armenian realities.

Then you have, if you address the post-Soviet and national and it goes against the global.

And you have, when it’s only good for national, and for me this is quite a hilarious kind of a not serious case, of a ‘ծովից ծով Հայաստան’ (tsovits tsov Hayastan, ‘sea to sea Armenia’, an expression used by Armenians to refer to the kingdom of Tigranes which extended from the Caspian Sea to the Mediterranean Sea) or something like that.

And all the other versions. We can talk a lot about that.

But I think this (is the) way (via this table); and keeping into account the need in this (a strategic who); and taking into account this (the rhizome and the ‘islands of change’ and their networks)…

And so my last word for this entire series will be: we have paid a lot of attention to how to deal with power: direct, violent, straightforward power structures.

We have paid much less attention, in all of our reform strategies, in all our considerations, in the amount of media publications, in the amount of people thinking - to education and culture. And they are regarded as something secondary to the power. Like, first it is politics, then economy, society and then only culture.

And this is not so.

I think the biggest amount of change effort should go into discussing what is education and what kind of culture are we building. And they are very much interrelated.

And, I don’t know, academia, science and creativity: they are very much parts of this. And then we will have a better, a changed situation.

But I do hope, Artak jan, that these separate entities, at least a little bit united (networks built among ‘islands of change’), when they do well thought-through projects, not ‘global’ ones, it does make sense.

Any last comments?

So, we came to the end of this entire series.

Congratulations.

Thank you for your attention.

Thank you everybody for your attention.

We will be continuing on, and thinking along these lines, on which projects to do and which projects not to do as individuals, and as Eurasia Partnership Foundation.

Please ask us, if you want to do a project, maybe we can sit together and discuss. And particularly the issue of education: what kind of education system do we need in the times to come? And this is very strategic, but also, of course, having more or less fair elections is also, while it’s tactical, but also good. But if we have good education, we will then have also good projects, good programs of the parties, you remember this chain that I was drawing, so it makes sense to have, to reform the education system very thoroughly.

We will have all these series available for free; we have their transcripts with quite a lot of references. We will have summaries of the transcripts; we will have keywords of the transcripts. So you can watch or read this or refer to this anytime.

And please come to us with the desire to meet and talk and chat and having discussions and participating in something.

Thank you again!

[1] Armenia 3.0 Understanding Armenia. 20th Century. Part 7 (Jam Session), Pages 1-6

[2] Armenia 3.0 Understanding Armenia. 20th Century. Part 7 (Jam Session)

[3] Armenia 3.0 Understanding Armenia. 20th Century. Part 7 (Jam Session), Pages 3-11

[4] Armenia 3.0 Understanding Armenia. 20th Century. Part 7 (Jam Session), Page 10

[5] Armenia 3.0 Understanding Armenia. 20th Century. Part 2 (Jam Session), Pages 7-10

[6] Armenia 3.0 Understanding Armenia. 20th Century. Part 1 (Jam Session), Pages 4-8

[7] Armenia 3.0 Understanding Armenia. 20th Century. Part 4 (Jam Session), Pages 9-10

[8] Please see some of our anticorruption projects: (1) In English; (2) in Armenian

[9] Should be 17, but still a ridiculous figure