This video was created on March 14, 2017

You can download the transcript of this video here.

Was created by Eurasia Partnership Foundation

Transcribed by Ani Babayan

Transcription completed on March 25, 2017

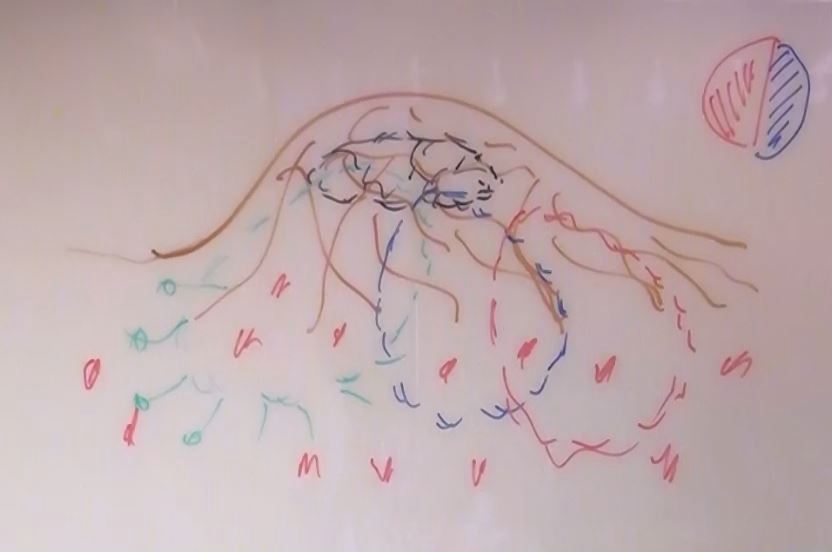

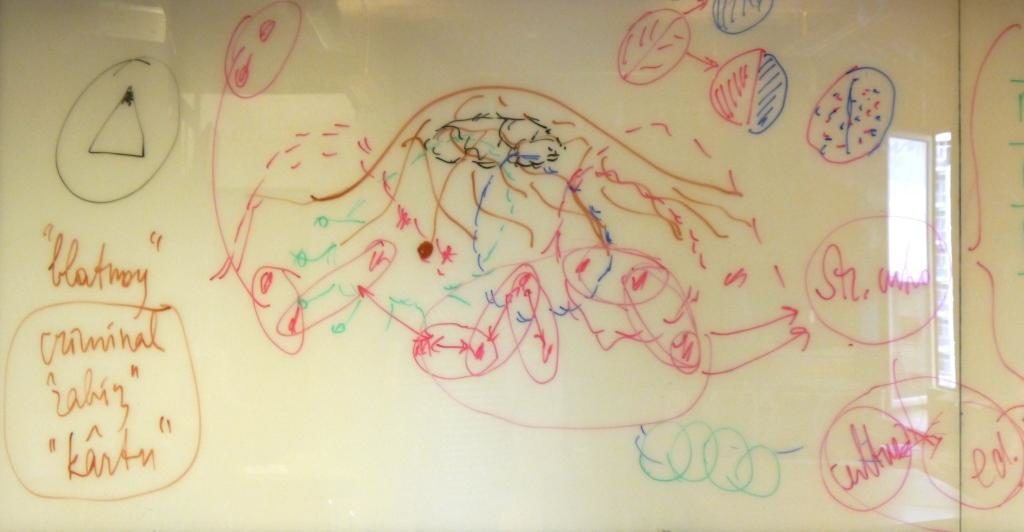

Gevorg Ter-Gabrielyan (GTG) - So, hi! This is going be another of our Jam Session Armenia 3.0 discussions; we are coming to a closure. We are now trying to summarize what we have talked about in the previous series. And I want to try to draw the type of the society that we have today. Of course, it is going to be a very rough drawing, as usual. But the way I imagine it, it could be presented like this flying (what is it called), flying plate, or whatever it is, which is the ‘rhizome’[1].

So, it is like, you know, all people interconnected here, via their allegiance to this or that structure, which is associated with the governance system. And, of course, we immediately come up with the question: whether or not this (the top, the ‘chapeau’) is the right top for the society, or there should be other tops. But we will talk about that.

So, within this overall rhizome we can see some particular rings, particular rings. This, for instance, this can be presented as the, as the police ring. This can be the church associated ring. And this can be the military associated ring. What are these rings? These are particularly strong structures within the rhizome, where people, who enter this area, like in the Armenian Apostolic Church service, or police service, or military service, they become also participants in the political economy of the country via other means and ways.

Why is that? Because these rings are easily absorbing people. Because it is one way of making one’s life more or less sustainable, relatively speaking, in Armenia. Because at least two structures are paid from the state; and church in itself also gives several opportunities for people to survive. So, you are somehow making the ends meet, nearly, via engaging in one of these structures. Plus to that you can have, just like it is in the rhizome, you can have the situation where a lot of opportunities are branching out from the fact that you participate in this rhizome. This may be small businesses, this may be extraction of money from somebody, this may be just providing opportunities to your families and friends, etc.

Of course, there are some other rings, as well. This is just, you know, the picture that I imagined. Because I see so many times that many small businesses belong to people who are either in this ring (church), or in this ring (police), or in this ring (military). You can also see other rings, like the educational system that we have talked about[2][3]. And, of course, you have here (on top), probably, the most, kind of, particular ring, which is the richest oligarchs and their interrelationships and, of course, it does not have to be one only ring, there are several interrelated ring.

So, what about the ordinary people? Well, let’s imagine that they are like this (red dots on the picture). They are everywhere, right? Our entire broadcast has been telling the story about the duality[4] in the soul of a typical Armenian citizen, be that in the 20th century, and be that in the 21st century. This duality, I am going to draw a coffee-bean like duality, so it’s one way of looking at it: it is like, it is like this (a coffee bean divided with a line into two parts).

So, on one hand, you have to participate in something unfair, in something, which is either legally, or ethically incorrect; on the other hand you try to be a nice person within the limits that are left to you. So, you, this is the issue which we talked, that in the situation where it is, it becomes extreme, it leads to some kind of a social schizophrenia[5].

In the situation where it is, you know, in (an)other situation it might, it may have a milder form.

In fact, of course, this picture (of the coffee bean) shouldn't be presented like this, but rather something like this (where the ‘good’ and the ‘bad’ are mixed), where both, I mean, it’s not, it’s not half-half, it’s more like ‘yin yang’.

You have this (a ‘good’ quality) and you have this (a ‘bad’ quality) inside one and the same person.

But the most important thing is that these two things (the two ‘selves’) are separated. There are several examples of that: you are a teacher, but you are corrupt, because during the elections times you are leading a precinct, electoral precinct, but you teach nice values, as if, to the children[6].

Or you are, you don’t want to kill people, you are a nice person, but you hate Azerbaijanis, and you, if you are in the army, you have to kill Azerbaijanis.

And you are a humanist in your soul, but you don’t think that many people in the world are human, and it is Azerbaijanis and Turks. In some cases, some people in Armenia also think the same about the Muslims in general, despite the entire historical experience to the contrary, of residing along with the Muslims and the living with the Muslims, of different nationalities.

So, this is another, this kind of, you know, adversarial relations of two types, of two sets of values inside one’s soul and many, many other things.

You are, as I was saying, from the ‘tsekhavik’[7] times, from the Soviet times: you are extorting money from others; you are taking bribes; you are giving bribes; but ‘for your family you are a nice man’, or woman, and you want your children to be nice people.

So, this is this controversy, which is kind of, you know, rampant in the rhizome. But these people that I mentioned (the red dots), these are those who may or may not be infected by that controversy, to a higher degree or to a lower degree.

So, in this situation, if you take now the approaching elections. What do we have? We have about 6-9, I don’t know how many parties and party alliances, of which they are almost non- distinguishable from one another. So, if you draw their interrelationship, the chain of their interrelationship, it will be something like this (overlapping circles). There is one party which is slightly away, or a party alliance, there’s another one which is at the, kind of, at the bottom of this chain; and the rest of them are pretty much linked to each other.

So, if you are looking at the elections from the perspective of the rhizome you can see, you can say that the main aim of these elections and the change of the governmental system is to strengthen the rhizome. I’ve already talked about that. So that, if previously only this circle (the main one) was in charge of the governing rhizome, now it will be this entire circle (the chain of circles), or a part of it, when they enter the parliament, which is in charge of governing the rhizome. So the rhizome will, in fact, expand, strengthen itself, become stronger. And there will be even less niches for these kind of people (unattached dots) to survive in this society.

That’s where this situation is being headed toward, in my opinion.

Now, what should these people (the unattached ones) do? Obviously, they should create alliances between each other. This can be people, this can be separate organizations, this can be separate entities, institutions. But essentially it is people, or small groups of people, families or whatever. So, they have to build alliances with each one, and they have to build so-called ‘islands of not belonging to the rhizome’. That’s the only way that they can resist to this.

And the rhizome, as I said, it’s getting everywhere, right? So, it’s very difficult to keep away from it, so this is a challenge for these categories (unattached) to build this kind of alliances. But essentially that’s one of the sound strategies to survive in this situation without becoming a part of the rhizome and without sacrificing your values; and somehow keeping some energy to, to move towards the change of the society.

So, the eventual result of this would be if other tops are being constituted thanks to these islands reuniting (additional truncated ‘tops’ are drawn on the picture).

So that it’s no more so visible and distinguished, this so-called ‘power elite’ in the society, that they are other recognized elites.

Why is it now quite impossible? Because in the situation of collapse of the all possible trust and values, the triangular, or the pyramidal shape of the society is a blueprint which is in everybody’s mind. So whoever has political power, the power for violence, is considered to be on top.

If we move towards this kind of society (with many tops), that is, that we will have some things that today are quite lacking: which is a cultural elite, scientific elite, I don’t know, any kind of other elites, who have quite some power, which is not necessarily installed via violence and via building the rhizome, but who have quite some power and can influence the, the kind of, movement of the society forward.

The last thing that I want to say about this situation, and this controversy between this type of people (in the rhizome) and this type of people (outside the rhizome) is that, it’s the so-called, the problem of ‘handshakability’.

We already talked about that: after Stalinist years, in a superficial way the ‘blatnoy’[8] culture was taken as one of the types of behavior in the society. And while in the Soviet times it was subdued, in the post-Soviet times it somehow became even more rampant. And all of the other types of behavior, which is like criminal circles’ (behavior). You know what we call ‘rabiz’ from the Soviet times. What is it called today? ‘Qyartu’. All these types are associated, obviously, with the blatnoy culture.

And we have talked a lot about the ‘donos’[9] (թուղթ գրել ինչ-որ մեկի վրա), ‘to write a paper if’ you translate it into English, about the, kind of, this renunciation culture.

Now, it is very interesting that in the blatnoy culture, that blatnoy culture is not the one which accepts donos. It is the contrary. It’s the one which denies the right of people to donos, it doesn’t encourage donos. It encourages keeping everything inside, it encourages being devoted to one’s ring, being devoted to one’s mafia, it doesn’t encourage to speak out.

Why is that? Because in the Soviet Gulag[10] system you had, the system itself was built on donos, so people were being beaten up, were being tortured in order to sign up, as if they have committed crimes; or to give names of their acquaintances, friends, relatives. To bring as many as possible people, to bring to the gulag system. So donos was encouraged by the authorities, while the blatnoy culture is originally something which is against the authorities.

blatnoy in the gulag system means ‘thief-in-law’, who doesn’t participate in, he doesn’t take orders from the gulag system, administration. He doesn’t participate in public works. He has a codex, he has rules to follow, that’s why it is called ‘thief-in-law’, and they are the blatnoy rules. Some of them never cooperate with the authorities, and those who cooperate are called ‘Freier’ (фраер), or something else.

Why is it that it’s not the Gulag system itself that has been inherited psychologically in the value system?

That is to say, the value system of the blatnoy culture (which has not been inherited directly)?

Because it also had an element of resistance in it.

So, when the blatnoy culture comes to top, when the blatnoy culture becomes the governing culture, what happens is that speaking up is discouraged, so donos, it is perceived as donos.

So, this is a typical situation which many of us may have been experiencing since the school times: when one child is beating up another child, and if this child reports, his friends, his schoolmates are telling ‘you are’… in Russian it’s called ‘ябеда’, you are a ‘գործ տվող’, you are a snatch (should be ‘sneak’). Yeah, it’s not exactly that word, but these are the kind of words that you are somebody who is giving information about something that shouldn’t have been known to the teachers.

So, this is exactly what is being installed here (in Armenia). So, on one hand, you have a culture which was based on donos to a very certain, very deep degree. On the other hand, you have a culture, the blatnoy culture, which came to power, which is prohibiting opening up, whistle blowing, opening up information, opening up issues, because people around you will say: ‘You are the, not the snatch, but the ‘ябеда’’ (the sneak), the guy who is, in Armenian they say ‘վառել’, who is ‘putting on fire’ everything, who is taking the skeletons out of the closet.

So, this is very obviously in the interest, this very much corresponds to the interest of the rhizome culture, because that means that you cannot really speak out, and that’s why the public space in Armenia is quite, not in a good shape. That’s why they very often say that there’s no public opinion in Armenia. When you measure public opinion correctly it gives a horrible picture, like 3% of people only trust the president, the police, the media, the NGOs, the medicine, everything, 3% only, as CRRC research shows.

When, however, you are living in the situation that everybody can claim that they did sociological research, you can have any figure; nobody trusts any figures at all.

The other phenomenon is that in the islands, where the freedom of speech is possible, like in the Internet, in Facebook, for instance, there’s the gap increasing between saying something and acting upon something. So any kind of investigative journalism results that Hetq publishes, for instance, which is the only, probably unique, entity which strategically publishes investigative journalism results for many years, any kind of other disclosures that take place in the public sphere, or in the remnants, you know, elements of the public sphere which exists, they don’t lead to any results.

So people who have to be prosecuted for being corrupt, they are running for parliament seats, so the gap between speech and deed, or the influence of free speech, or opening up the issues for decision making is totally absent.

That’s another phenomenon here, which, again, the only way to, kind of, to, obviously, to overcome it, is to establish more and more connections between these islands (the little networks of likeminded people who are outside the rhizome and have become connected).

To the extent that these alternative elite structures (alternative truncated tops/chapeaus) become more capable of action.

And it can be done in different ways. One way, which is known from the Soviet, post-Soviet tradition, and is not a way of, you know, of criminal prosecution, but of the ethical attitude: is the issue of shaking hands or not shaking hands with some people.

So, in Russian it’s called ‘рукопожатность’ (ձեռքսեղմելիություն in Armenian), ‘handshakability’.

The problem is that in this situation many people are facing the issue of either saying ‘hello’ to this kind of people, or not saying ‘hello’ to this kind of people. And this is a big issue of course.

So, in this blatnoy culture those who want to keep away from being blatnoy have to think about, whether or not they are going to the compromise of participating with people who are like this (in the rhizome), or who are like this (partly attached to the rhizome, divided) in anything, in work for reform, in just living in the same space, relating to each other, etc.

If you have strong public opinion, sometimes this kind of ‘anti-handshakability’ of somebody can become a good lesson for that person. But you don’t, there is no strong public opinion. So even if people build these semi-networks, partial networks, these small alliances between each other and they support each other, but when they are meeting this kind of people, when they are meeting this kind of people, very often they have to go to a compromise.

For instance, I personally have built for me a compromise, which looks like this: I don’t shake hands with people who are most likely either killers, or people who gave orders to kill. I don’t shake hands with people, who have stolen from the society X amount, something which is equal to X amount of money. I don’t have that amount in my mind, but it’s a big amount. If we are coming down to somebody who has stolen ten thousand dollars approximately for a good cause, for a compromise solution to work on something, I may have to swallow it and shake his hand or her hand. And if it’s somebody who has given bribes because they were forced to, I’ll be more tolerant toward these people, though I would prefer them not to do that. It is very difficult to live in this society and not to do that.

So, this ‘handshakability’ issue is another very interesting issue, which is present in this society.

So, when the Diaspora people come here and are very happy, because they are being met by high-level people who are on top of this rhizome pyramid; and they are very happy, because they are being invited to some parties with these high-level people; I don’t know if they realize or not that very often they are shaking hands which is better not to shake. I think in some cases they realize, but when it’s far away, when it’s distant, when it’s not your own country and you don’t know it from the inside, you somehow overlook that. But I wouldn’t be able to do that, when it comes to this kind of people, either in my country, or in any other country.

I mean if you are talking about the European politicians, very often it’s not a problem, these people have never really killed anybody, or given orders to kill anybody. It is quite rare, right, in European politics to have this situation? And even if it is this situation because an army is sent somewhere, it is very much legitimized by several other considerations, though eventually it’s again not very good, because it is people who went somewhere and participated in killings.

It is slightly different in America, because you had Guantanamo and that stuff. Of course, we should take into account that it was after 9/11, and in general the United States is quite different in terms of political violence. But in our part of the world it is very rare to find somebody who is either in Armenia, or in any other post-Soviet state, or any other surroundings, even not necessarily post-Soviet states, who is here, on top of this pyramid, and is not, has not participated in committing ‘legal’, ‘legitimate’, according to their legislation, or illegitimate gross human rights violations, gross crimes. This is something that one should take into account when dealing with this situation.

So, the healthy part of the society - it has been squeezed off, it leaves its own country. Of course not only the healthy part leaves the country, but many of them, it is getting smaller, it is shrinking. So that is one of the biggest problems here.

And the other, maybe the last, the last kind of a value element that I want to mention in this respect in the blatnoy culture. One was the prohibition of speaking out, the whistle blowing; the other was the issue of ‘handshakability’; and the other one which is very much being connected with that is ‘քցել’, it’s ‘to let down’, it’s to renege on the commitments.

Because of this trust collapse or, rather, the other way around, the causal relationship here is like chicken and eggs. But essentially we have trust collapse. Which means that very often most of the accords, agreements are likely to collapse, nobody trusts nobody, and people are ready to renege on many, many, many agreements.

An example from my day before yesterday situation: somebody is doing renovation above my apartment, and it’s very noisy, and I say to him, ‘please don’t throw the ‘շինարարական աղբ’, the construction garbage out of the window in the car, lorry, because the dust will come into our apartment’. He says, “Yes, yes, of course, I will use the other window, which doesn’t hinder you”, and he brings the lorry right there and does exactly that (that he promised not to do). Probably, with pleasure.

So this thing, to renege on any kind of accord, to, kind of, express the anti-humanness of lack of respect to the other, is rampant in this society. But as a consolation, I should say that in some other post-Soviet societies you have some other places where it’s even higher (this problem).

And it’s wrong to say (model) big societies as a united place, because Russia, for instance, can have very different types of behavior in different parts of Russia. But I have seen in Russia such level of the same inclination to let each other down that in Armenia you still have a better situation. Why? Because it’s a smaller society and people are not alien to each other. They may be interconnected to each other, and when you start speaking, explaining that element, that, ‘you know, today you didn’t follow our agreement that you will not dust my apartment, and tomorrow you may be asking me for something, for instance, to teach your children, or something like that; and then I’ll do the same with you’, - when you explain this - visibly, in front of our eyes the situation very often changes.

Another example, again, from my very recent experience. I needed one meter of a wire. So, I went to the market where there are all types of wires being sold. And I was asking everybody to sell me one meter of wire. And there are like seven, one after another, several sellers. And none of them gives me one meter. Because everyone says: ‘We have this entire bundle (which is 50 meters), so it should be something significant that we cut it’.

So, nobody wants to give me one meter of wire. So I walked: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, everybody refuses. When I approached the seventh one and he refuses again, I say: “Look, how much do you consider the minimum amount that you will sell”. He says, “Ten meters”. I say, “Okay, give me ten meters, I’ll return you nine as a gift. It’s not a big money, but I need one meter”. He says, “I don’t need any gift”. And then I say, “Okay you don’t need any gifts, but if I were you I would just give that one meter to me as a gift and say: ‘Of course, you are welcome, please take this one meter and go’ ”. And the guy said, “Okay, I’ll give you that one meter”. And he did that.

So, in front of our eyes, and there are other people present, the guy realized the level of petty lack of normal attitude to the customer, or just to another Armenian and to another human being, that was taking place, and he changed his mind.

Now, I am sure if we would do the same with the seven of these sellers, probably 3 or 4 of them would do the same as this guy did. So it was just because I wasn’t daring to ask the first ones, I was thinking that I’ll find it, that’s why it was happening.

So, this culture thing. And, of course, the one way out of it is education that we will be talking about next.

But before I move, because I think I have finished the entire picture, it’s quite daunting, but it has some hopes to go forward.

And now we are going to talk about what to do and how to do things if we do things.

So, this is, kind of, we are approaching a watershed between diagnoses versus what to do.

And again, we are not going to talk in many details on what to do, but, again, some kind of methodological suggestions and summing up of some of the stuff that has been said in the previous series.

But if you have any comment before that, please go ahead. And I see Mikayel wants to comment.

Mikayel Hovhannisyan (MH) – Actually I have one point related to… (If I may come to the whiteboard.) Actually the problem with creating these new ‘rhizomes’ or new (GTG – ‘anti-rhizomes’), whatever it is, it is a structure, which requires resources. The problem is that these subjects are obliged to fit this structure. So, in order to create a new one, it should find from somewhere additional resources, because this structure will have to fit it anyhow and find these additional resources for creating this one. So, in case of Armenia, this is quite a significant problem, because of that, very often lots of new structures are not being created, because of the lack of resources, which is being taken by the major structure.

And the second thing I wanted to say is that after the collapse of the Soviet, blatnoy came here (on top), but came in the form of the Soviet structure. So it filled - the blatnoy field - the politburo structure, which makes the situation even worse. Because it completely destructs the whole logic of building relations, making decisions, etc., etc.

So the thief-in-law rules that also have some pieces of justice inside, etc., etc., are completely destructed because of being filled in a completely different form, which doesn’t have this justice system, or has something that is completely different. So the situation is even worse. Thanks!

GTG – Yeah, it is a theatrical, it is a façade reality[11] we have talked, and we have been talking about, this dual reality: that one thing is presented instead of the other thing, indeed.

As for the resources, the only way for resource acquisition and resource accumulation, if this is the way, in the situation of behavior of building alliances, islands of change, islands of alternative situation, is: the more people join into the network, the more resource is being freed up. So, in general, that’s the direction, it is a never ending game. It is not so effective, it is always much more effective to destroy something than to build something; and it is more effective to be violent than not to be violent. So this is not a very effective road, but if it takes place then resource starts accumulating gradually. Because when we are talking about these islands, we are also talking about many small scale businesses, business people who don’t want to engage in this rhizome, they are trying to be somehow away from it to a certain extent. They are in a compromise situation, but they are still, they have this positive value, this positive capacity. Okay, Bella, you want to say something.

Isabella Sargsyan (IS) – Just a small thing to continue what Mikayel has said. I think in case of Armenia, this is the case when numbers matter. Because when you are looking to Russia or Belarus, (from) where people are leaving, but still in amounts they are still big societies. Million people who have left, in the case of Armenia, when you have, let’s say, 3 million people, and those who are leaving, as you said, quite often are those independent people - and then it becomes very, very difficult to generate (solidarity).

Especially, to me, it is a deliberate strategy, also to eliminate those (unattached people), deliberate, not just it happens because it happens, But this rhizome or the top of rhizome is deliberately working to eliminating all this kind of elements who are not part of it. So, I think, the numbers matter, and that there is another big risk, that a bigger rhizome can absorb you, coming, I don’t know, from the north, or from the east, I don’t know, from wherever, it just might absorb you if you don’t have enough, just enough people. It is not just about resources, but just physical people, who either leave or become the part of rhizome in this way or another, or they just get demoralized, if we can call it so. I mean people who simply have no moral resources to resist, so I think it is even worse, I think.

Robert Ghazinyan (RG) – I think, in terms of blatnoy elite that you talked about, I would also argue that in this past 25 years the blatnoy elite has been also combined with national, traditional behavioral patterns of Armenians; and it is now some kind of a mix of blatnoy part and this national behavioral, traditional, patriotic, national behavioral patterns. And I would argue also that the blatnoy part is decreasing and the other part is increasing. Because, for example, in the role of women, one can say that in blatnoy culture, the role of women is much bigger, and these women are free, much freer, than in Armenian blatnoy traditional behavioral pattern mix. So, yeah I think the blatnoy part is decreasing, the other part is increasing.

GTG – Thank you, Rob. The issue of blatnoy culture is very important issue in social sciences, because you have to look at its origins in the Tsarist Russia, in Odessa… One source of its origination is this kind of Jewish, or façade Jewish circles, again, people who were marginalized. But a very important push into that came from Central Asia, Azerbaijan and Caucasus during the Soviet times; and also North Caucasus and South Caucasus. I have seen numbers about 10-15 years ago, that the biggest amount of prison wards, camp wards, ‘вертухай’, in the North Caucasus, were people from Ossetian nationality.

Why? Because they were Christian, and they have been historically a pro-Russian nationality, mostly. They are not all of them Christian, they are divided, but a major part of them is. And so, the other nationalities: Chechens, Kabardinians, etc., and Ingush, they also hate Ossetians because of that: because they were the ones who were put in prison, and who, combining their national tradition of lack of statehood, or this kind of, you know, alternative to the state structures, with the blatnoy culture, with the thief-in-law psychology, which means you have ethics, you have traditions, you have rules of behavior, but you don’t participate in the big picture, you don’t relate to the authorities… And both of them are significantly based on violence: violence as a way of stopping violence, but still it is violence. In the Caucasian traditional cultures, like the blood revenge, etc., and in the blatnoy culture, where it is the stronger one who is leading.

So, there has been this entire influx of the blatnoy culture, also promoted by Stalin, who himself was Georgian-slash-Ossetian, and his cronies like Beria, etc. There has been this influx of the Caucasian and Central Asian, of these Eastern traditions in the blatnoy culture. It’s a very interesting topic to study, in fact. And in addition to that, the façade reality, the fake reality is also very much coming from the East, form Central Asia, from the Caucasus. As you know, most of the fake dissertations in the Soviet times were being done by people who belong to the nationalities of Caucasus or Central Asia, because they could bribe the commission and as if defend a dissertation. So you had a lot of fake doctors with fake diplomas, a lot of fake scientists, a lot of; etc.

What happens today in Russia, and very often with Russians themselves, is something that was inherited from the Soviet times, when it was more typical for the Eastern nationalities. And why is that? Because the system, the bureaucratic system of the Soviet Union, or of Russia, did not correspond to their internal value system. Because in these Eastern societies, it was traditional to give ‘baksheesh’, to give something (մաղարիչ - magharich) in reply of a service. It wasn’t something which was legally or morally wrong, right?

So, in the situation where the power was installed on them from top, that (baksheesh) became illegal from the perspective of this power, and from the perspective of certain alternative ethical value system, like of the nations which were more to the west. But that wasn’t illegal from the perspective of the East.

So they tried to spoil, to corrupt others, which is a very typical behavior of corruption, corruption spread via this rhizome[12].

Why is that? Because you see that from the perspective of certain group of people, or of certain percent, this is not morally wrong. And this is not… or maybe it is illegal, but who is paying attention to the law. So, you think: if it is not morally wrong for these people, and they are quite nice people, and they are quite authoritative, why should it be wrong for me? This is how it’s spread. So there is… it is a scholarly topic to study deeper, but a very interesting one.

So, the only reply… Of course we are giving quite a bleak picture here. But well, we are a global nation, right?

So, the only reply I have is, those who are in today’s situation… those who are away don’t have to be away, they can be participants. They can come and go, they can relocate. And that’s why relocating here, in any case, is the right choice for the Diaspora to help Armenia. Just visiting is not enough, relocating is the right choice.

And again, you know, Diaspora too… You can have this kind of people in the Diaspora (ethically mixed) and you can have this kind of people (unattached to the criminality). And we have talked about that: many people who have left the Soviet, post-Soviet Armenia, they took the criminal and blatnoy traditions with themselves to the West.

So, it is important for this kind of people (unattached to the criminality) to relocate to Armenia. But this kind of people (ethically mixed) they usually relocate to a place where they can make money.

It was in Russia 20 years ago, when a lot of tricksters and a lot of adventurers went there. In Armenia, today, there are not many opportunities for adventure, for big buck, and stuff like that.

But I encourage people who are clean with their conscience to relocate to Armenia. But also if they can’t, or they don’t plan to, establish ties for a longer term period.

[1] Armenia 3.0 Understanding Armenia. 20th Century. Part 1 (Jam Session), Pages 4-8

[2] Armenia 3.0 Understanding Armenia. 20th Century. Part 1 (Jam Session), Pages 3-6

[3] Armenia Elections: Over 100 Schools Accused of Illegal Campaigning, Civilnet

Some detailed article in Armenian by Civilnet: Դպրոցների ու մանկապարտեզների տնօրենները ձայներ են հավաքագրում ՀՀԿ-ի համար

[4] Armenia 3.0 Understanding Armenia. 20th Century. Part 3 (Jam Session), Pages 8-10

[5] Armenia 3.0 Understanding Armenia. 20th Century. Part 3 (Jam Session), Pages 9-10

[6] Դպրոցների տնօրենները հետ են զանգել ու բողոքել, հայ հաքերները հարձակվել են կայքի վրա. Դանիել Իոաննիսյանը՝ սպառնալիքների մասին

[7] Armenia 3.0 Understanding Armenia. 20th Century. Part 2 (Jam Session), Pages 12-13

[8] Armenia 3.0 Understanding Armenia. 20th Century. Part 2 (Jam Session), Pages 7-10

[9] Armenia 3.0 Understanding Armenia. 20th Century. Part 2 (Jam Session), Pages 2-10

[10] Armenia 3.0 Understanding Armenia. 20th Century. Part 2 (Jam Session), Pages 4-11

[11] Armenia 3.0 Understanding Armenia. 20th Century. Part 3 (Jam Session), Pages 9-10

[12] This is a common practice in the criminal world of creating esprit de corps, or collective responsibility (круговая порука) to cover up crimes via recruiting ‘unattached’ people in the criminal rings and behavior, absorbing them in the rhizome, immersing, ‘initiating’ them in crime and then blackmailing them that they are now as guilty and/or as ‘dirty’ as the others, and therefore they cannot denounce the crime. Interestingly, this practice, in terms of its action – engaging people in something, often against their will, the engagement in which defines the change in their social position and makes the latter irreversible—has parallels with another blatnoy/criminal practice—degrading/humiliating people (‘putting down’, опускать) which has been common in closed male environments of the Soviet Union—prisons, Gulag camps, the army—and has been inherited in the first years of the Armenian army (garlakh, գառլախ), though this practice is being actively fought against in today’s Armenian army.